Gabriella Richardson is an Impact and Learning Manager at Gakino’amaage. Passionate about educational equity and community-led initiatives, Gabby works closely with First Nations schools to support meaningful Indigenous-led programs and research. Her recent trip to Petit Casimir Memorial School in Northlands Denesuline First Nation provided an opportunity to connect with educators, learn about the community’s rich Dene language program, and explore how cultural revitalization and language learning are being integrated into the classroom.

Gabriella Richardson is the Impact and Learning Manager at Gakino’amaage.

In April 2024, I had the privilege of visiting Petit Casimir Memorial School in Northlands Denesuline First Nation. My original purpose was to discuss a potential parental engagement research project, but during my time there, I was introduced to something truly inspiring—the school’s Dene language program, which embodies the heart and soul of Denesuline culture.

Since the school’s opening in 1995, the Dene language program has been a pillar of pride, nurturing the language that carries the knowledge, stories, and traditions of the Denesuline people. The dedicated Native Language Teacher, Fred, has been a part of this journey since Vice Principal Linda Inglis herself was a student. With deep roots in the language, Fred’s expertise extends beyond the classroom, having once assisted the government with Dene translation work. His deep commitment to preserving and promoting the language shines through.

An example of the Dene language resources carefully crafted by Fred and his team.

It quickly became clear during my visit that Dene is not just a subject taught in school—it is a living, breathing part of the students’ daily lives. The language flows through conversations in the halls, between staff and students alike. Each morning, Fred leads the school in a prayer spoken in Dene over the intercom, setting a tone of respect for the language and culture.

It quickly became clear during my visit that Dene is not just a subject taught in school—it is a living, breathing part of the students’ daily lives.

Fred’s approach to teaching is creative and adaptive, recognizing the importance of making language learning enjoyable and accessible. For the younger students, from kindergarten to grade 3, he emphasizes oral language acquisition through songs and repetition. One morning, I had the joy of witnessing the kindergarten class enthusiastically singing songs that Fred had translated into Dene for an upcoming school concert. The children’s excitement was infectious, and Fred’s method of weaving the language into music ensured the children were learning, perhaps without even realizing it. As Fred shared later, these songs often remind parents of their own childhoods, creating intergenerational connections that are key to revitalizing the language.

For students in grades 4 to 8, the focus shifts to writing Dene in Roman orthography, and by high school, students begin tackling the challenge of learning Dene syllabics. When I arrived, high school students were working on writing a story about the legendary Dene hero Thanadelthur, blending traditional storytelling with their growing language skills—a beautiful example of how the language continues to evolve while honoring the past.

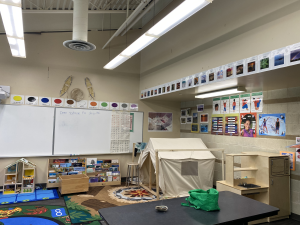

Stepping into the Dene language classroom felt like entering a sanctuary of cultural pride. The smell of sage filled the air, as teachers popped in and out, consulting Fred for guidance on how to express something in Dene. It was clear that this space was much more than a classroom—it was a hub of knowledge-sharing and community.

The Dene Language Classroom at Petit Casimir Memorial School in Northlands Denesuline First Nation.

Fred and Linda walked me through the rich array of resources they’ve built over the years. The walls were filled with chart papers displaying Dene songs, numbers, colors, and everyday objects, all meticulously labeled in Dene. There was even a scrabble board with Dene words and a display board featuring plant species with their traditional Dene names—tangible ways for students to connect with the language and land.

A unique Dene Scrabble board offers a fun and interactive way for students to build their vocabulary and deepen their connection to the language.

Of course, like all efforts in language revitalization, challenges persist. Fred and Linda explained that finding suitable teaching resources can be difficult, and much of what they receive requires significant adaptation to reflect the specific dialect of their community. Regardless of these challenges, they persevere.

A list of Dene syllables, one of the many resources Fred and Linda have developed over the years, displayed proudly in the classroom to support students in learning to read and write in Dene.

Fred is excited about the future—plans are in place to integrate more technology into his lessons, showing videos of Elders speaking Dene and even encouraging students to record interviews with family members in Dene, collecting oral histories that will be preserved for future generations. In the fall of 2024, Fred will also receive the invaluable support of an Education Assistant, which will further enrich the program and help him design a curriculum tailored to the students’ needs.

When I asked Fred how he felt about his role in this movement, his response was hopeful: “I really enjoy teaching the language because I want the students to know it. The language has been decreasing, but it’s heartening to see it become more popular again.” His words encapsulate the spirit of revitalization, reminding us that every step forward is a victory for the language and the culture it carries.

The Dene language program at Petit Casimir Memorial School is a testament to the power of education as a tool for cultural preservation and renewal. The dedication of Fred, Linda, and the entire school community reminds us that with passion, dedication, and creativity, Indigenous languages can continue to connect generations and shape the future.