Teach For Canada’s Summer Enrichment Program brings teachers together with Indigenous leaders, northern teachers, and education experts to prepare them to support student success in northern First Nations in Ontario and Manitoba. Since 2020, the Summer Enrichment Program has been fully digitized as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

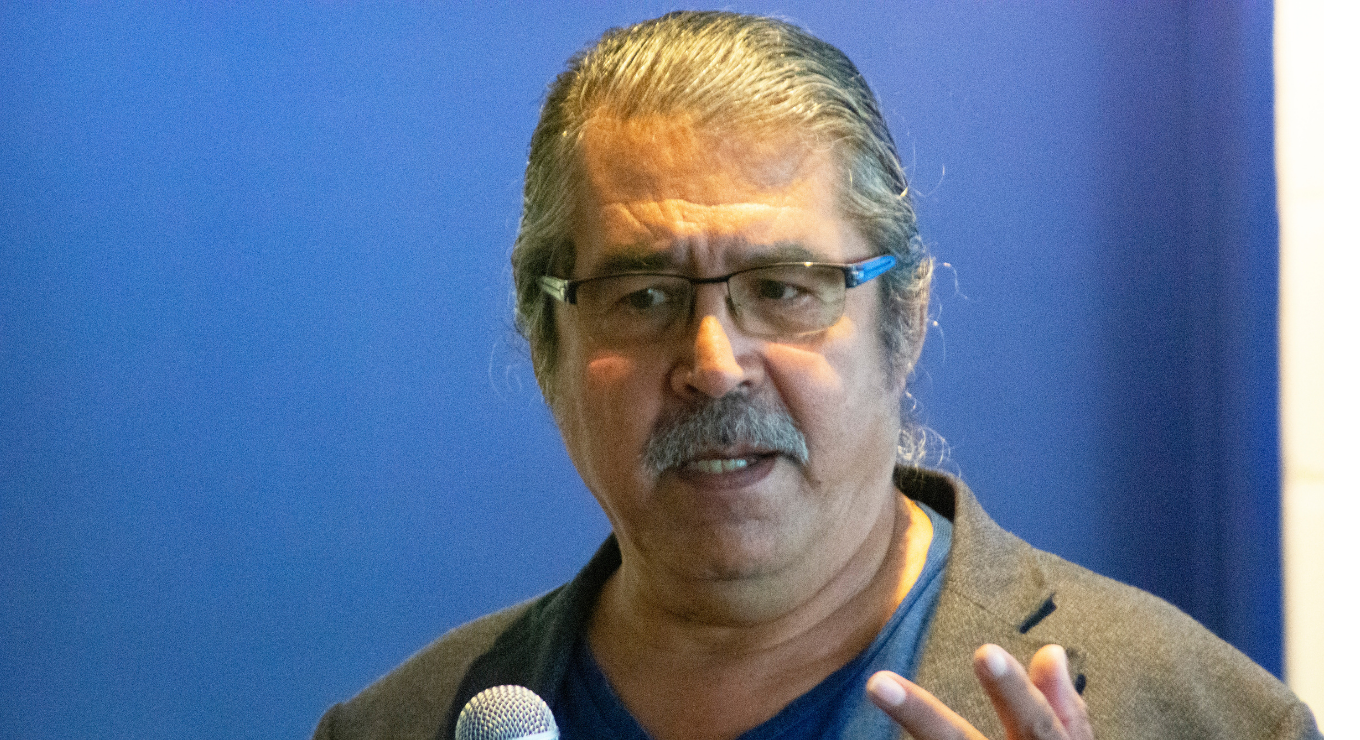

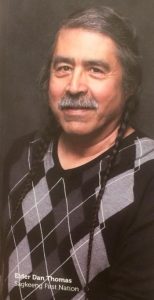

Dan Thomas presented on Indian Residential Schools and Intergenerational Trauma as part of the 2021 program. Dan is an Elder and Instructor at the University of Winnipeg, where he serves as Elder-in-Residence at their Aboriginal Student Centre and the Seven Oaks School Division.

Elder Dan Thomas presented on Indian Residential Schools and Intergenerational Trauma at Teach For Canada’s 2021 Summer Enrichment Program

Teachings centered around Indigenous histories are a significant part of Teach For Canada’s Summer Enrichment Program. Providing educators with a foundational understanding of the historical treatment of Indigenous peoples in Canada is imperative to preparing educators for their time in the North.

We are grateful for Elders like Dan who have taken the time and courage to share their stories. Dan is a survivor of Manitoba’s first Provincial residential school, the Frontier Collegiate Institute. He spoke with Teach For Canada educators to share his story, explain his experience navigating historical trauma, and share some steps that we may take to begin to heal.

Residential Schools in Canada

Residential school students in a typical classroom. (Photo courtesy Truth and Reconciliation Commission / Anglican Church Archives, Old Sun)

“A school on every reserve.” This was one of the many treaty promises that the federal government knowingly and willingly broke.

Not only were First Nations not granted education infrastructure in their communities, but their children were uprooted from their homes to attend residential schools thousands of kilometers away. These children, many as young as 6 years old, were taken at night from spaces filled with love, humour, and honour to institutions that were cold, sterile, and abusive.

This was the reality for over 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children in Canada, including Elder Dan Thomas.

Since the first residential school opening in the early 19th century, Canada has operated approximately 130 residential schools, the most recent closing its doors in 1996. Around 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children were removed from their communities and forced into these government-funded, church-run facilities.

Here, many faced cruel conditions such as severe malnutrition, abuse at the hands of teachers and staff, and a lack of adequate medical care. With the knowledge and approval of the federal government, some schools conducted nutritional experiments on students without the knowledge or consent of the subjects or their parents. As a result of these inhumane conditions, over 6,000 children were known and recorded to have died at Indian residential schools.

According to the 1907 Bryce Report, the mortality rate in western Canada’s residential schools was an annual 52%. In 2021 alone, the remains of more than 1,600 children have been found so far, with many school sites to be searched.

What is Historical Trauma?

Historical trauma, also referred to as intergenerational trauma, is trauma faced by a specific cultural group as a result of historic systematic oppression. When these traumas are ignored and no support is offered to those experiencing it, they are passed down to the next generation. In this way, unhealthy, harmful or destructive trauma-induced behaviours become normalized and remain in families. As Elder Thomas puts it, “this cycle becomes a norm, but it is far from natural.”

Canada’s Indigenous communities have suffered consistent traumas since the 1400s. In the past 500 years, communities were decimated by mass deaths, with some losing up to 90% of their populations. These deaths were caused largely by disease, invasion of and expulsion from their homelands, loss of economic self-sufficiency, removal of children from homes, brutal assimilation tactics, and residential school incarceration.

The traumas that Indigenous communities have faced have been further compounded by the intentional destruction of Indigenous culture, art and community, which eliminated traditional healing and coping mechanisms. Loss of ceremonial freedom, dance, song and use of sacred medicines meant that Indigenous people were unable to properly express or grieve their losses.

In his session, Elder Dan Thomas shared his experience navigating intergenerational trauma. When he encountered triggers that reconnected him to his time at Frontier Collegiate, he would experience extreme physical and emotional distress. Fortunately, Dan was able to identify his trauma and work to process it. Many others remain unable to do so.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Elder Dan Thomas closed his session by sharing what he believes are the necessary next steps to address the historical trauma faced by Indigenous peoples across Canada. Below are his suggestions on how we may work towards a better, more just future.

Commissioned by the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions (TRC), this Coast Salish Bentwood Box was carved by artist Luke Marston. The box represents the distinct cultures of former residential school students, and stands as a tribute to all Indian Residential School Survivors. Photo courtesy of the University of Manitoba.

Listen and acknowledge

Before any healing can occur, survivors must release their traumas. But to do this, there must be a genuine acknowledgment of the truth. The Canadian government must prioritize real action and take concrete steps toward reconciliation. For real change to occur, it is not enough for residential school survivors to process their traumas. As Elder Thomas states, we all have a part to play.

Learn and unlearn

Non-Indigenous Canadians must do their part in understanding the historical treatment of Canada’s First Peoples. Canadians must make ongoing efforts to educate themselves on Canada’s unfavourable history and the dark truths this nation holds. They must work to learn and unlearn the histories of Canada from the perspectives of First Nations.

“If enough of us change,” Elder Thomas insists, “we’ll reach a tipping point. This is what is needed to see real change. We must accept nothing less than changed behaviour at all levels of society.”

The role of Educators

Educators must teach Indigenous children how to think instead of what to think. They must empower and encourage Indigenous kids to be proud of who they are.

When possible, educators should take steps to thoughtfully integrate Indigenous knowledge, values and teachings into their curricula. Culturally responsive lessons, like land-based learning, can pass on meaningful knowledge to new generations and strengthen the pride and Indigeneity of students.

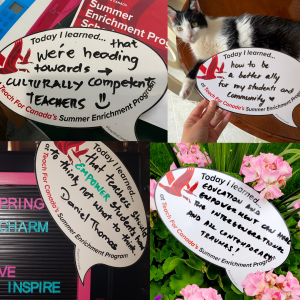

Participants were encouraged to reflect on their learnings following the presentation.

Interested in learning more about this year’s Summer Enrichment Program? Click here.