Jason Singh is going to be the principal at Michikan Lake School, Bearskin Lake First Nation, starting in September 2018. Jason completed a Bachelor of Science and a Bachelor of Education at York University, and is currently working on a Master of Education at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE). Jason has experience as a Science teacher and principal. He is originally from Toronto.

Jason Singh is going to be the school principal in Bearskin Lake First Nation

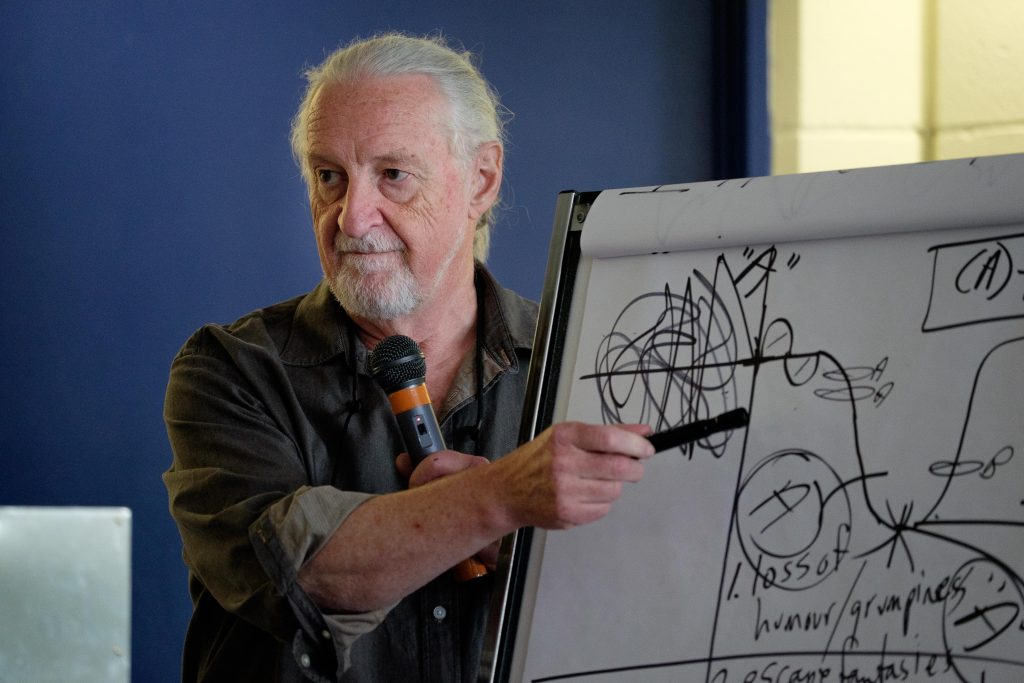

This summer, 47 educators from around the world came together to begin their journey into Northern Ontario, and I am privileged to be one of them. It started with the Summer Enrichment Program, throughout which we were challenged physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. We all began the three-week preparation program with hopes, fears, and fantasies, and, as presenter Randy Weekes predicted in his session on cultural adjustment, these developed over the weeks that followed.

Randy Weekes helps teachers prepare for cultural adjustment in the North

Entering the Summer Enrichment Program, I hoped that I would create positive change by helping educated students; feared that I wouldn’t be accepted by the community; and fantasized that reconciliation would move forward with our participation.

Challenging my Understanding of Canada

Throughout my Kindergarten to grade 12 education in Ontario, and even during my undergraduate degree, the “us versus them” narrative has been used to exoticize Indigenous communities in Canada. My understanding of First Nation, Metis, and Inuit (FNMI) communities was first challenged when I began my graduate studies at OISE, leading me to pursue a career in the North. The Summer Enrichment Program did not let me down in bringing this narrative to the forefront and challenging everything I thought I knew about Indigenous cultures in Canada.

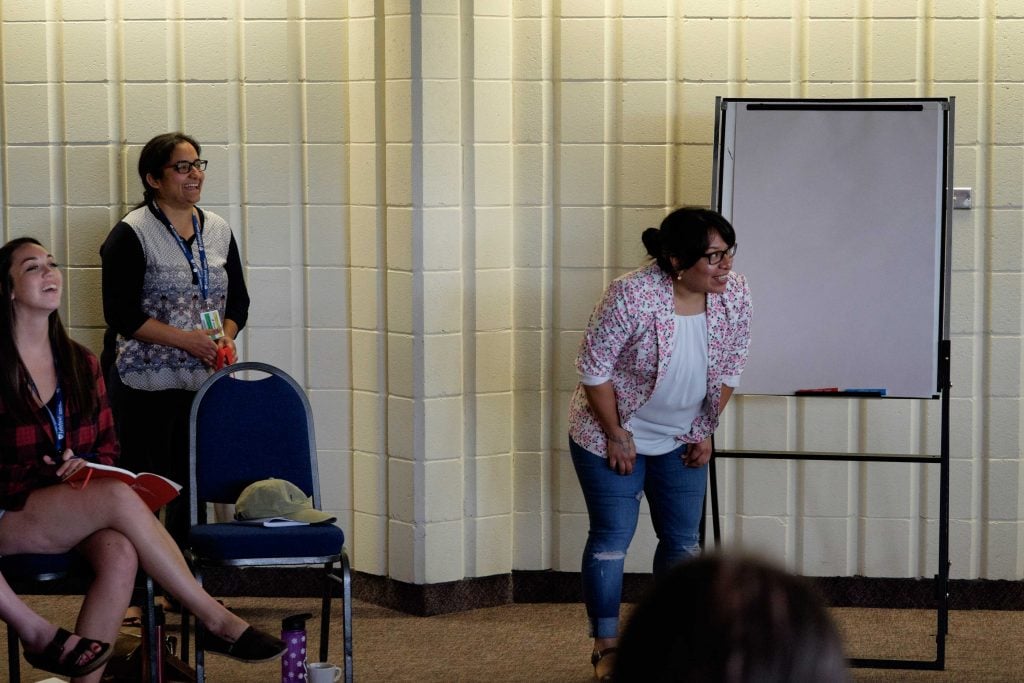

Maria Montejo presents “Exploring Perceptions and Worldviews”

As a high school science teacher, presenter Maria Montejo’s analysis of Western sciences objectives to “control, dominate, and measure nature” really made me step back and question my own feelings and beliefs. A quick analysis of the grade 11-12 Ontario Science Curriculum document sees the words control and measure written 56 and 54 times, respectively. I didn’t really expect to see dominate in there (but was open to the possibility). Indeed, the Western world is one of assessment, and everything needs to be categorized to perpetuate the illusion of control. Conversely, Indigenous science understands that everything is connected, and our perception of the world is created by life experience, not by knowledge. As we prepare to transition into the North, First Nations educator and presenter Dan Thomas implored the cohort: “Don’t teach the curriculum, teach our children. Teach them how to think, not what to think.”

A New Understanding of Reconciliation

Western culture has sought to suppress this, as Maria Montejo recognized that curiosity in children is often suppressed, and curiosity is a prerequisite to intelligence. This suppression ran deep with the residential school system and continues with the significant overrepresentation of Indigenous children in the Canadian foster care system.

This was an epiphany for me, as I realized that I am not part of something that has happened in the past and that is being “fixed”. I am part of something that is ongoing. We are not at the reconciliation step of this journey – we are still building trust, and “change moves at the speed of trust,” as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder expert and presenter Allan Montford, explained to us.

Jason Singh comes to a new understanding of reconciliation

As the only principal at the Summer Enrichment Program, I viewed a lot of the wisdom shared from a different perspective than my peers, but was humbled by the common learning we all experienced. From the start of the program, I was wondering how I could possibly create positive change in the community. How would I be able to use my knowledge and skill set to help kids learn and help the school grow?

Teach For Canada’s Chancillor Crane (left) helps Jason Singh understand his role as a principal

Then I met Teach For Canada staff member Chancillor Crane. If I could choose one word to describe Chancillor, it would be visionary. He was able to share ideas with me that put me in a better place and reminded me that I will not change anyone – people have to change themselves. His most influential teaching was that of a flowing river representing the direction community takes. As a principal, I will never stop that river from flowing. I may be able to divert it, like a pebble in the water, but it will keep on flowing. Instead of trying to stop it, he encouraged me to flow with it. This I will always remember.

Going North Ready and Supported

As we move into the final weeks before flying out to the First Nations where we will be living and working, I am comforted knowing that it is okay that I do not have all the answers. I have 46 amazing people, the Teach For Canada staff, and all my family and friends to reach out to, and I hope they know they can reach out to me as well.

Jason Singh and Teach For Canada teachers on a hike during the Summer Enrichment Program

Thinking back on Randy Weekes’s words, I now hope that I will contribute positively to students’ education in Bearskin Lake First Nation. I no longer question whether or not I will be accepted. I am headed to a warm and welcoming community and am ready to learn. I still fantasize that reconciliation will move forward, but I know this will be through the building of trust. If I had to sum up my learning in a single phrase, it would be: have no expectations; have only an open mind and an open heart.